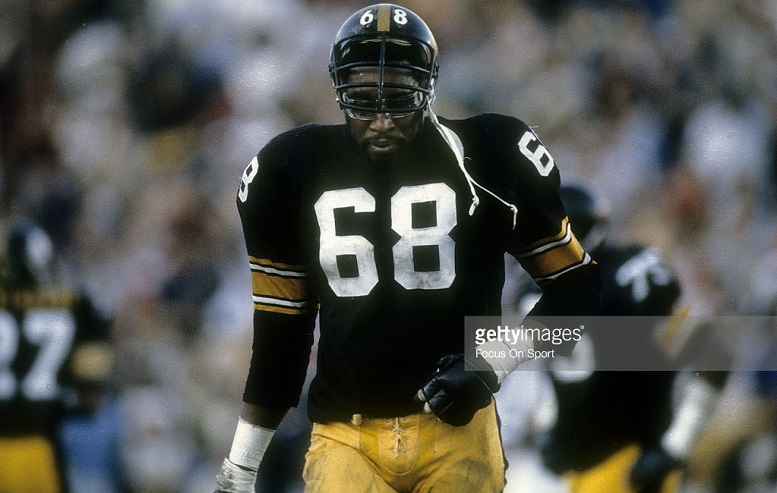

NFL won’t help family of late Steelers guard Justin Strzelczyk, but it finds solace in support group.

Justin Strzelczyk has been gone for more than a decade, but the pain from his death in a fiery head-on collision on the New York State Thruway in 2004 continues to ripple through his family, his ex-wife Keana McMahon says.

The former Steelers offensive lineman, one of the first NFL players diagnosed with CTE by pathologist Bennet Omalu, led troopers on a 40-mile high-speed chase before he drove into oncoming interstate traffic and collided with a tanker truck.

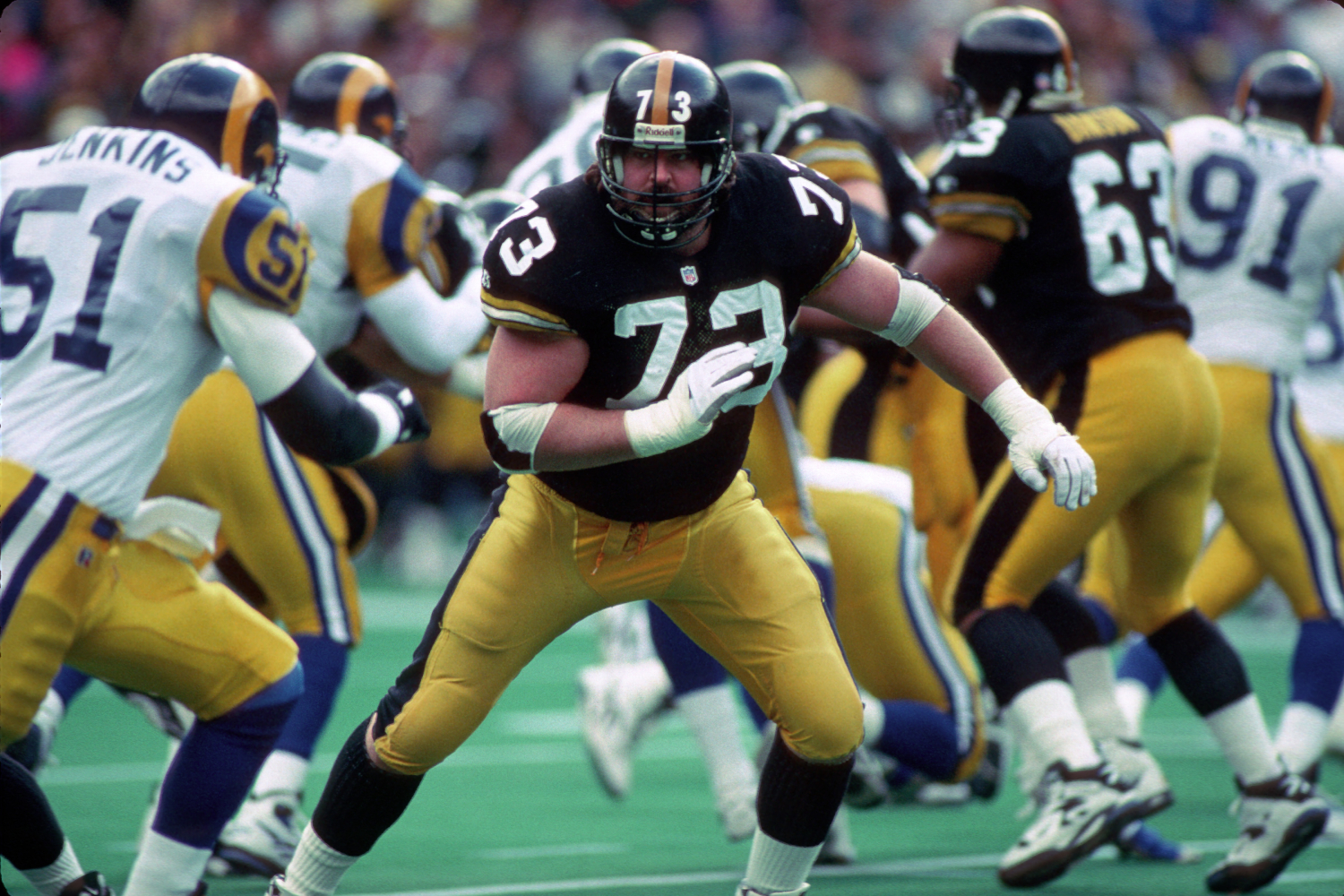

Their daughter Sabrina, now a student at a Pittsburgh art school, required years of therapy to deal with Strzelczyk’s death. Their son Justin Jr., now a student at George Washington University, was outwardly stoic but emotionally devastated. Strzelczyk played nine years for the Steelers in the 1990s, but the NFL and the Steelers have done nothing to aid his family, McMahon says.

“Bill Cowher didn’t even come to Justin’s funeral,” she says of the ex-husband’s longtime NFL coach. “That still makes me angry.”

McMahon has found help dealing with her own anger and grief by working with Sisters in Sports, a support group for the families of athletes founded by Karen Moyer, the wife of longtime Major League Baseball pitcher Jamie Moyer.

The organization, McMahon said, regularly receives calls for help from the wives of NFL retirees whose husbands are struggling with depression, dementia, mood swings and other symptoms of CTE, the league’s brain-destroying industrial disease linked to the deaths of Strzelczyk, Mike Webster, Junior Seau, Andre Waters and other former NFL players. They often turn to Sisters in Sports because the league and its teams don’t respond to their calls for help.

“We get these calls from women – ‘he’s crazy, he’s depressed.’ People think these guys are wealthy, like they have Fort Knox in their basement, but a lot of these families need money and they need emotional support,” she says. “There is no help for these women. The NFL drops the ball once these guys leave the game.”

The players’ families have to take care of each other, she says, because the NFL, the Players Association and the teams do not. The NFL is an enormous economic engine, but little of that money trickles down to ex-players in need. The NFL’s pending concussion lawsuit settlement won’t benefit her kids, she says, because players like Strzelczyk who died before 2006 are not included in the deal.

McMahon, who divorced Strzelczyk in 2001 due to his mood swings and erratic behavior and later remarried, says she can’t watch NFL games because of the damage she saw football do to her ex-husband and other players. She won’t watch the Super Bowl between the Panthers and the Broncos.

“It makes me sick, the hell these players go through,” she says. “Get drunk, eat your food and watch the game, but I don’t want any part of it.”

McMahon says current NFL players should demand lifelong health insurance. Strzelczyk and his teammates didn’t know about CTE but current players do, she says. “Justin wore the same helmet for years,” she says. “Pittsburgh never replaced the helmet, his helmet was shot. He didn’t know what he was getting into. Now the players do, and they still won’t get the help they need.”

McMahon said “Concussion,” the film that portrays how the NFL tried to discredit Omalu and his CTE research, accurately portrays her life with Strzelczyk, Webster’s Harley-riding teammate. The only false note, she says, is in the scene that shows her ex grabbing her by the throat. Strzelczyk’s outbursts frightened her and the kids, but she says he never struck her.

“It was very accurate, although there could have been more to it,” she says. “Things got simplified for the movie. But the trauma is real and it lasts for years.”

Leave a Reply