After the Giants used a loophole, J.D. Davis was released and lost the majority of his $6.9 million salary.

When the most recent Collective Bargaining Agreement was approved before the 2022 season, Major League Baseball players celebrated what they saw as a long-awaited win. One-year contracts with full guarantees would now be available to players who meet the arbitration threshold, which includes most players with more than 2 1/2 but less than six years of service time.

However, there was a weakness. And it didn’t take a group long to take advantage of it.

That team was the Giants. J.D. Davis, a third baseman, was the one who got caught.

In a stunning turn of events, the Giants cut relations with Davis on Monday by placing him on unconditional release waivers. Davis had defeated them in an arbitration hearing in February, earning a $6.9 million contract. Giants owe Davis just thirty days of termination salary, or slightly over $1.1 million, because the CBA clearly states that arbitration salaries determined during a hearing are not guaranteed.

Many in the industry will perceive this unusual choice as callous and heartless. Some will see it as a reasonable choice that respects teams’ rights under the CBA. There is no denying that Davis, who played in a team-high 144 games the previous season but was rendered unnecessary with the signing of third baseman Matt Chapman, a free agent, was put in an uneasy situation two weeks prior to Opening Day: he had no team and was suddenly only paid 16 percent of the salary that an impartial panel had just determined he was worth.

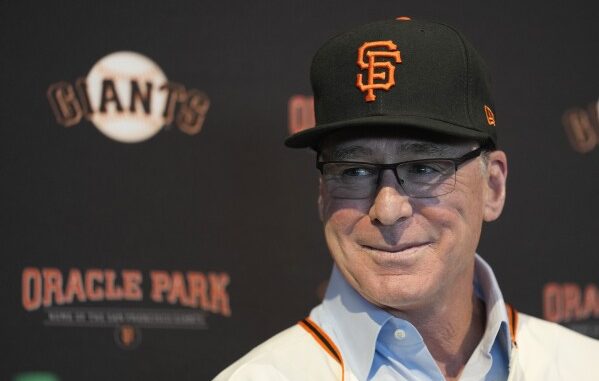

Farhan Zaidi, the president of baseball operations for the Giants, told reporters during a hurriedly scheduled Zoom call on Monday that the team tried and failed to move Davis. This past weekend, the Giants placed Davis on unconditional waivers, hoping that a different team would pick him up and expedite the process.

“We made this decision as soon as we learned he went unclaimed on outright waivers,” Zaidi stated. “It all comes down to role and the other guys we had with more at-bats than J.D. We would keep every player if our roster numbered 28 or 30. But we had to make this decision given the reality of our roster limitations.

“As a team, everything we’ve done in this case has been well within our rights,” Zaidi said. And it is acknowledged. The CBA is extremely cut-and-dry.

The question will be how much of the Giants’ exploitation of those regulations was deliberate and how frequently it happened.

The Giants have recently chosen to follow the “file-and-trial” strategy that has spread around the league, wherein teams and players exchange pay estimates to be presented before a hearing, and after that point, all discussions come to an end. According to Zaidi, the strategy is designed to prevent talks from proceeding to the hearing level. Prior to the hearing, Davis stated last month that he would have gladly taken the $6.55 million filing figure from the Giants. However, following the exchange, the team was unwilling to resume negotiations.

The Giants “negotiate all our arbitration cases in good faith,” according to Zaidi, who stated on Monday that Davis could have accepted the club’s offer before the figures were exchanged.

Matt Hannaford, Davis’ agent, refuted that description. According to Hannaford, GM Pete Putila texted Davis an offer, which the Giants accepted, an hour before the filing deadline. According to Hannaford, the club’s offer was “hundreds of thousands” less than the amount the team had applied for.

Hannaford stated, “In my 22 years in the industry, I’ve never seen a club in arbitration make their one and only offer that ended up hundreds of thousands of dollars below their filing number less than an hour before the exchange deadline.” “J.D. was forced to attend a hearing, which we won, due to the Giants’ negotiating tactics.”

Davis, who is currently a free agent without restrictions, was not expected to have a grievance to submit, according to industry insiders.

Hannaford expressed his confidence in J.D. as a player and the value he will bring to his next team, despite the club’s bad handling of the situation. “When all is said and done, I know he will find himself in a better situation.”

The Giants formally made Davis an offer that was “just slightly under $6.4 million, matching the raise of what we believed to be one of the most relevant comps in the case,” according to Zaidi, who was asked to verify Hannaford’s testimony. Zaidi stated that the club did not view it as the best-and-final offer, but the representatives of Davis failed to provide a formal counter offer or even a response until ten minutes prior to the deadline. Instead, they merely stated that the number “has to start with a 7.”

“They filed at $6.9 million after that, and they called a few hours after the deadline, hoping to work out a settlement,” Zaidi stated. “We said that we were not in a position to negotiate once the exchange deadline had passed, both in fairness to our other negotiations and to maintain credibility with our policy going forward.”

Whether the Giants intentionally guided this particular result to ensure that Davis’ pay would not be assured, they had essentially purchased a cheap insurance policy in case they couldn’t reach an agreement with Chapman, an Oakland manager Bob Melvin-affiliated third baseman who had won four Gold Gloves and was a Scott Boras client. Given that he and Davis were teammates at Cal State Fullerton, the Giants’ signing of Chapman on March 3 to a three-year, $54 million contract with two opt-outs might have made for an endearing tale. However, it was clear that Davis’ time on the team was running out as Wilmer Flores and Jorge Soler occupied all of the right-handed at-bats at first base and designated hitter.

While Zaidi expressed no regret for the decision made on Monday, he did admit that the club’s inability to find a buyer for Davis’ salary was a regrettable result of the drawn-out talks with Chapman.

Zaidi stated, “This might have been different if the wheels had been put in motion earlier this offseason, but that’s just the reality.” “When you’re this far down the road, it’s harder (for teams) to take on significant chunks of payroll.” So, it shouldn’t come as a huge surprise. It has been evident in a couple of the recent free-agent deals. The market isn’t the same as it was during the off-season.

The Giants would have been responsible for 45 days of termination pay, or $1.66 million, if Davis had been let go before 15 days before the season began. By letting him go after 17 days, they were able to save around $500,000.

Although it is uncommon, teams do occasionally cut players who are eligible for arbitration before the season begins. Infielder Todd Walker was cut by the San Diego Padres in the spring of 2007, just over a month after he was given a $3.95 million contract by an arbitration tribunal. Instead, Walker was paid $971,311 in termination benefits. Left-hander James Russell of the Atlanta Braves and right-hander Justin Grimm of the Chicago Cubs are two additional recent examples of players who were released by their organizations in the spring and lost the majority of their paychecks in the $2–3 million area. Todd Greene, the then-catcher for the Anaheim Angels, was taken by surprise when the team fired him before to Opening Day in 2000, giving up $180,556 of his $650,000 contract.

With the loss of around $6 million, Davis becomes arguably the most well-known example ever.

In the event that free agency continues to develop slowly, more teams may decide to shuffle their rosters during spring training and sign arbitration-eligible players who were perhaps more solidly in the team’s plans over the winter. It’s now evident that teams benefit greatly even in cases when they lose, despite Zaidi’s insistence that the “file-and-trial” method is intended to discourage hearings.

The Players Association will almost definitely want to have that phrase changed in the next agreement, even if Davis ends up being the only player caught under the loophole.

For the time being, the Giants have reduced their payroll responsibilities by around $6 million and are currently about $13 million below the $237 million initial luxury tax threshold.

Zaidi refuted the idea that the Giants’ reputation would suffer among free agents and their own players due to the harshness of Davis’ decision.

“I disagree wholeheartedly,” Zaidi declared. “Talk to the players on our team about how the organization treats them, about the communication with the manager, coaching staff, and front office,” Zaidi said. This spring, Zaidi was came under fire after veteran shortstop Brandon Crawford made disparaging remarks.

“On this topic, I firmly disagree. No matter what the reason, breaking up with a player is usually painful and feels personal to them. Having worked for three different companies, I’ve seen this a lot. It’s just the way things work on the business end. Although you can tell people in the front office that something is never personal, I know that from the perspective of a player, it will always feel personal. It’s both their life and work.

“In general, I believe that players have the right to voice their dissatisfaction, irritation, disappointment, and feelings of mistreatment to some extent, and we won’t engage in a public back and forth about it. However, I would strongly object to that being taken as a generalization about the organization. If you don’t think my word is sufficient, ask athletes in our organization about the degree of communication and how they feel the organization looks out for them. We place a great deal of importance on these items.

Leave a Reply